For stuff like this YouTube is great. I wonder how long it’ll stay this way?

This gig finds the Police in their high-octane early incarnation, quite neo-punk, in terms of energy. It’s more confusing than appearances might suggest though, as they are, essentially, a power-trio. Quite a rock-mongous beast! But whereas most power trios would have an axe-wielding guitar-hero, Any Summers is more art-rock weirdo, and the instrumental star is really Copeland.

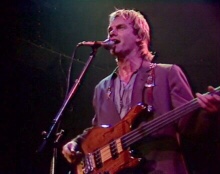

Sting is, well… Sting, bankably good looking and charismatic (as Andy Summers wryly observed from the get go), with a brilliant voice, song writing skills to die for, and seemingly born to the role of frontman. Not in an Elvis or Ozzy way, but just by being himself. Fantastic!

Personally I love their mellower side, the first real sign of which is the mesmeric Bring On The Night. It’s still way more pumped than the Regatta de Blanc album version. But the ethereality and the melancholy of the Sting aspect of the group is allowed to simmer and come to the boil wonderfully.

Also very notable is the jazz-prog side of the group, not in overt ‘genre’ terms, but in the fact that songs are frequently allowed to breath in extended passages of improvisation. For example, in Bring On The Night they go into a totally intense double time blast variant that I’ve not heard on any other performances.

Also very intriguing are tracks like Fall Out and Visions of the Night, which are not part of The Police’s album canon. But when they return to the more familiar material, with Bed’s Too Big Without You, they go into a blinding cosmic über-jam that finally resolves back into the song. And the go waaay out! Astonishing!

One of them, Sting, I think, is triggering some synth effects, and Copeland’s drums often get treated to washes of dubby delay. so they generate a massive sound. And this despite not having a conventional lead spanner of a guitarist. Summers can cut loose with the blues rock style thing, as he briefly does on a Bullet train from Japan version of Peanuts.

This is a young band, riding the crest of their burgeoning stardom; btheir energy is super intense. I think Stewart Copeland is a very large part of this. And what a monstrous driving drummer he is! His kit, like his his playing is unique. His use of hi-hat and tide so much more expressive than the average rock/pop drummer. And his fills and use of odd accents, literal splashes of sound, and the octobans and roto-toms, all add up to a unique voice in driving seat.

Roxanne is also put through the extended-improv wringer. The German crowd are wigging out. And who could blame them. What a performance. Even the rather approximate tuning of Sting’s bass can’t put a dampener on proceedings.