Strictly speaking I shouldn’t bother with this. At least not in my current series of posts on Jobim’s solo albums. So, strictly speaking this isn’t part of that series. But as it was on the list of solo albums I started off with, and remains on the Wikipedia list of Jobim’s solo albums, and is included as part of a five album/CD set … I’m going to write it up now anyway.

The arrangements are by Lindolpho Gaya (?) and Eumir Deodato, the latter also playing piano. Other than the presence of his picture on the cover, and the allusions to his name, twice in the albums title/subtitle, the only other things that might locate this in a series of Jobim-related posts are the inclusion of two of his compositions, and the presence of Edison Machado on drums, who played the same role on Jobim’s genuine debut, just a few years earlier.

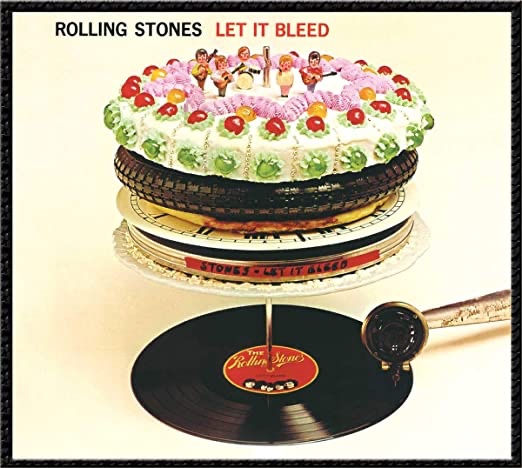

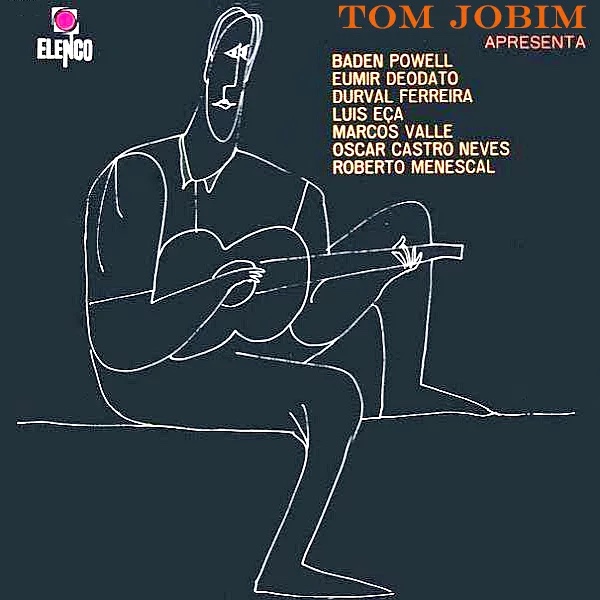

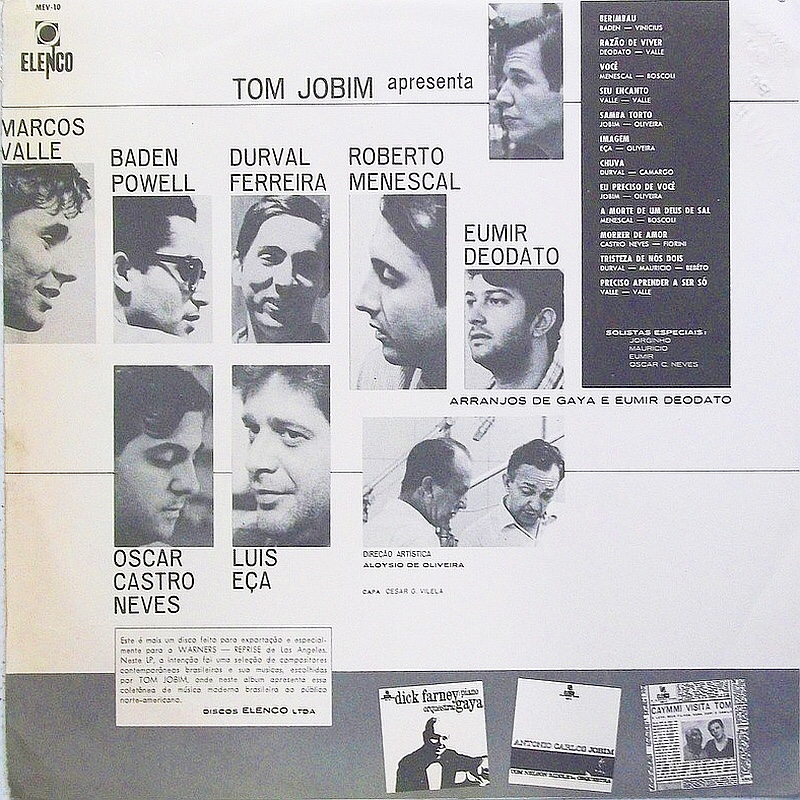

Anyway, (kind of) moving on from the Jobim series I’m currently writing up, let’s dive into this on its own merits. But, before we do that, let’s address this mis-attribution issue. How and why has this come to be thought of as a Jobim recording? Basically it’s down to the US music biz marketing folk. The Brazilian original, on the Elenco label, told a more honest story (see the two pics below).

As can be seen, the original idea was to use Jobim as the ‘familiar face’, and via his success or celebrity, introduce new Brazilian talent to a wider audience. With typical marketing department crassness, however, this morphed into outright misrepresentation, in pursuit of sales.

Initial US releases not only plastered Jobim’s name everywhere, but credited him as both pianist and guitarist, despite the fact he isn’t on the album as a player at all, but rather as the composer of just two of the twelve tracks.

And even those two tracks are presented here under their English titles, for the US market: Eu Preciso de Voce becomes Hurry Up and Love Me, and Samba Torto is renamed Pardon My English (and both are arranged by ‘Gaya’, about whom I know nothing).

The contrast between the more exotica flavoured opener, Hurry Up And Love Me, which is rambunctious, and the more authentically mellow and laid back bossa nova vibes of tracks two, If You Went Away, and three, the latter the slightly more upbeat jazzy waltz Seu Encanto (or The Face I love), both composed by Marcos Valle, and both arranged by Deodato, is very striking.

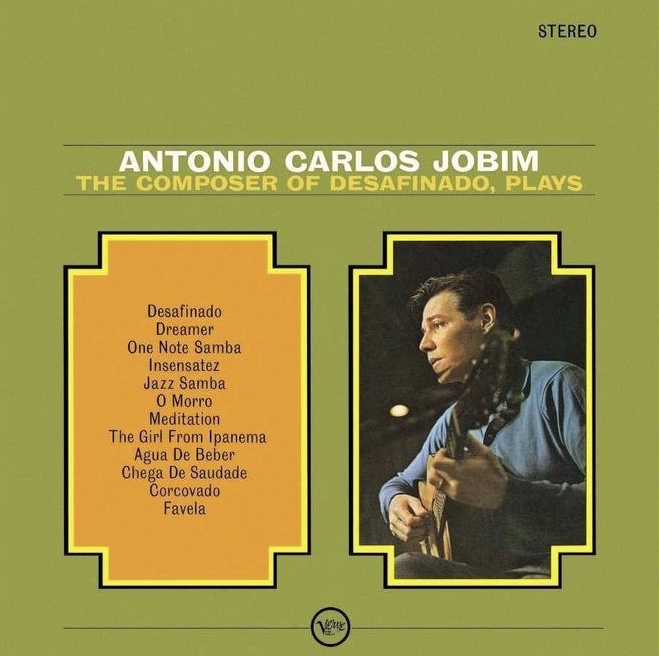

Deodato’s arrangements are much more in keeping with the Jobim/Ogerman style, as heard on The Composer of Desafinado Plays.

After Jobim, the two artists/composers most likely to be known outside Brazil are pianist and arranger Eumir Deodato, whose arrangements on this disc are – as just noted above – terrific/very authentically bossa nova, and the then very young Marcos Valle. Other featured artists include Baden Powell, Luiz Eca and Roberto Menescal, and others. Baden Powell’s classic Berimbau gets a good outing, with a pretty fabulous Deodato arrangement, more dramatic and even cinematic than typical of the rest of the album.

Track seven brings Jobim’s work back, but in an odd arrangement, whose exotica stylings – parping low-register brass! – tip over into the overtly comical. Not your typical Jobim stylings at all. This is, I suspect, the mysterious Gaya again. Once again the contrast when we return to the more authentic bossa stylings of Durval Ferreira’s Chuva (Rain) are very striking. This latter number is also notable for the unusual use of harmonica as a melodic lead voice.

A Jobim purist might be annoyed by the con-job of passing this album off as a Jobim solo disc, and it is in itself a bit of a mixed bag, not just on account of being the work of multiple composers, but that of more than one – and quite differing in style – arrangers.

The Deodato arranged stuff is, fortunately, both more plentiful and just plain better/more suited to the material. All of the compositions are presented here, as indeed are the all-Jobim selections on his Composer Plays debut, as instrumentals. And whilst not quite of the uniformly high standard of Jobim’s own such stuff, the other material here does share enough Brazilian bossa/samba DNA to be worth having.

So, bit of a mixed bag, and definitely neither essential, nor a good place from which to start an appreciation of Jobim’s musical genius. But still worth having if you’re a lover of this style and era of Brazilian music, as I am.