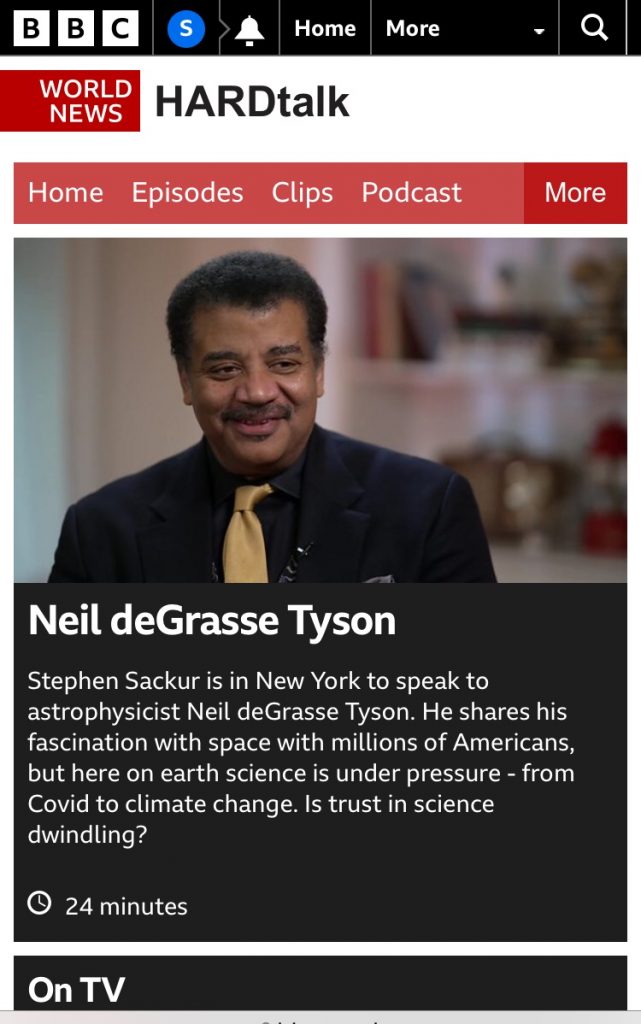

Just caught the last five or ten minutes of this. Fascinating! Neil deGrasse Tyson might be described as an heir to Carl Sagan, inasmuch as he’s a populariser of science, and a New Yoiker.

I’ll definitely be checking out the full interview at some point.

Several things stuck me, about Tyson (or should that be deGrasse Tyson?)*. First off I’m on his ‘team’, so to speak. His bit about open-mindedness reminded me of Dawkins’ thing about being so open-minded your brain falls out!

Returning momentarily to the Sagan allusion I made above, another thing about the astrophysicist that was less appealing than his very reasonable eloquence and knowledge was his rather booming slightly overbearing style.

Folk like Sagan, and in other areas of science, Attenborough, even Richard Dawkins, are (if you actually watch them in public discussion, as opposed to basing your views on the hearsay of their ‘adversaries’) pretty scrupulous in their attempts to be calmly and politely evenhanded, or reasonable. Neil deG&T, on the other hand, exhibited moments of what looked to me worryingly like controlling bluster in his responses to some of Stephen Sackur’s questions.

* Americans are big on middle names. Very notably so in public and intellectual life (one of the themes of this interview concerns the state of the latter in the modern US). But, although I’ve not seen it hyphenated, deGrasse Tyson sounds like a double-barrelled surname.